American Pie (song)

| "American Pie" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

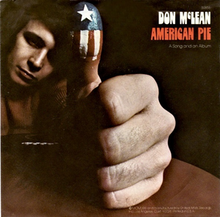

U.S. vinyl single. Artwork was also used as the front cover for the album of the same name and many other international releases of the single. | ||||

| Single by Don McLean | ||||

| from the album American Pie | ||||

| B-side |

| |||

| Released |

| |||

| Recorded | May 26, 1971 | |||

| Genre | Folk rock[1] | |||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | United Artists | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Don McLean | |||

| Producer(s) | Ed Freeman | |||

| Don McLean singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "American Pie" on YouTube | ||||

| Audio | ||||

| "American Pie" on YouTube | ||||

| Live video | ||||

| "American Pie live performance on BBC, July 29, 1972" on YouTube | ||||

"American Pie" is a song by American singer and songwriter Don McLean. Recorded and released in 1971 on the album of the same name, the single was the number-one US hit for four weeks in 1972 starting January 15[2] after just eight weeks on the US Billboard charts (where it entered at number 69).[3] The song also topped the charts in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. In the UK, the single reached number 2, where it stayed for three weeks on its original 1971 release, and a reissue in 1991 reached No. 12. The song was listed as the No. 5 song on the RIAA project Songs of the Century. A truncated version of the song was covered by Madonna in 2000 and reached No. 1 in at least 15 countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia. At 8 minutes and 42 seconds, McLean's combined version is the sixth longest song to enter the Billboard Hot 100 (at the time of release it was the longest). The song also held the record for almost 50 years for being the longest song to reach number one[4] before Taylor Swift's "All Too Well (10 Minute Version)" broke the record in 2021.[5] Due to its exceptional length, it was initially released as a two-sided 7-inch single.[6] "American Pie" has been described as "one of the most successful and debated songs of the 20th century".[7]

The repeated phrase "the day the music died" refers to a plane crash in 1959 that killed early rock and roll stars Buddy Holly, The Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens, ending the era of early rock and roll; this became the popular nickname for that crash. The theme of the song goes beyond mourning McLean's childhood music heroes, reflecting the deep cultural changes and profound disillusion and loss of innocence of his generation[7] – the early rock and roll generation – that took place between the 1959 plane crash and either late 1969[8] or late 1970.[9][10] The meaning of the other lyrics, which cryptically allude to many of the jarring events and social changes experienced during that period, has been debated for decades. McLean repeatedly declined to explain the symbolism behind the many characters and events mentioned; he eventually released his songwriting notes to accompany the original manuscript when it was sold in 2015, explaining many of these. McLean further elaborated on the lyrical meaning in a 2022 documentary celebrating the song's 50th anniversary, in which he stated the song was driven by impressionism, and debunked some of the more widely speculated symbols.

In 2017, McLean's original recording was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[11] To mark the 50th anniversary of the song, McLean performed a 35-date tour through Europe, starting in Wales and ending in Austria, in 2022.[12]

Background

[edit]Don McLean drew inspiration for the song from his childhood experience delivering newspapers during the time of the plane crash that killed early rock and roll musicians Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and The Big Bopper:

I first found out about the plane crash because I was a 13-year-old newspaper delivery boy in New Rochelle, New York, and I was carrying the bundle of the local Standard-Star papers that were bound in twine, and when I cut it open with a knife, there it was on the front page.

— Don McLean[13]

McLean reportedly wrote "American Pie" in Saratoga Springs, New York, at Caffè Lena, but a 2011 New York Times article quotes McLean as disputing this claim.[14] Some employees at Caffè Lena claim that he started writing the song there, and then continued to write the song in both Cold Spring, New York,[15] and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[16] McLean claims that the song was only written in Cold Spring and Philadelphia.[14] Tin & Lint, a bar on Caroline Street in Saratoga Springs, claims the song was written there, and a plaque marks the table. While a 2022 documentary on the history of the song claims Saint Joseph's University as where the song was first performed,[17][18] McLean insists that the song made its debut in Philadelphia at Temple University[14] when he opened for Laura Nyro on March 14, 1971.[16]

The song was produced by Ed Freeman and recorded with a few session musicians. Freeman did not want McLean to play rhythm guitar on the song but eventually relented. McLean and the session musicians rehearsed for two weeks but failed to get the song right. At the last minute, the pianist Paul Griffin was added, which is when the tune came together.[19] McLean used a 1969 or 1970 Martin D-28 guitar to provide the basic chords throughout "American Pie".[20]

The song debuted in the album American Pie in October 1971 and was released as a single in November. The song's eight-and-a-half-minute length meant that it could not fit entirely on one side of the 45 RPM record, so United Artists had the first 4:11 taking up the A-side of the record and the final 4:31 the B-side. Radio stations initially played the A-side of the song only, but soon switched to the full album version to satisfy their audiences.[21]

Upon the single release, Cash Box called it "folk-rock's most ambitious and successful epic endeavor since 'Alice's Restaurant.'"[22] Record World called it a "monumental accomplishment of lyric writing".[23]

Interpretations

[edit]The sense of disillusion and loss that the song transmits isn't just about deaths in the world of music, but also about a generation that could no longer believe in the utopian dreams of the 1950s... According to McLean, the song represents a shift from the naïve and innocent '50s to the darker decade of the '60s

Don called his song a complicated parable, open to different interpretations. "People ask me if I left the lyrics open to ambiguity. Of course I did. I wanted to make a whole series of complex statements. The lyrics had to do with the state of society at the time."

The song has nostalgic themes,[25] stretching from the late 1950s until late 1969 or 1970. Except to acknowledge that he first learned about Buddy Holly's death on February 3, 1959 – McLean was age 13 – when he was folding newspapers for his paper route on the morning of February 4, 1959 (hence the line "February made me shiver/with every paper I'd deliver"), McLean has generally avoided responding to direct questions about the song's lyrics; he has said: "They're beyond analysis. They're poetry."[26] He also stated in an editorial published in 2009, on the 50th anniversary of the crash that killed Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J. P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson (all of whom are alluded to in the final verse in a comparison with the Christian Holy Trinity), that writing the first verse of the song exorcised his long-running grief over Holly's death and that he considers the song to be "a big song... that summed up the world known as America".[27] McLean dedicated the American Pie album to Holly.

Some commentators have identified the song as outlining the darkening of cultural mood, as over time the cultural vanguard passed from Pete Seeger and Joan Baez (the "King and Queen" of folk music), then from Elvis Presley (known as "the King" of Rock and Roll), to Bob Dylan ("the Jester" – who wore a jacket similar to that worn by cultural icon James Dean, was known as "the voice of his generation" ("a voice that came from you and me"),[28] and whose motorcycle accident ("in a cast") left him in reclusion for many years, recording in studios rather than touring ("on the sidelines")), to The Beatles (John Lennon, punned with Vladimir Lenin, and "the Quartet" – although McLean has stated the Quartet is a reference to other people[6]), to The Byrds (who wrote one of the first psychedelic rock songs, "Eight Miles High", and then "fell fast" – the song was banned, band member Gene Clark entered rehabilitation, known colloquially as a "fallout shelter", and shortly after, the group declined as it lost members, changed genres, and alienated fans), to The Rolling Stones (who released Their Satanic Majesties Request and the singles "Jumpin' Jack Flash" and "Sympathy for the Devil" ("Jack Flash", "Satan", "The Devil"), and used Hells Angels – "Angels born in Hell" – as Altamont event security, with fatal consequences, bringing the 1960s to a violent end[29]), and to Janis Joplin (the "girl who sang the blues" but just "turned away" – she died of a heroin overdose the following year).

It has also been speculated that the song contains numerous references to post-World War II American political events, such as the assassination of John F. Kennedy (known casually as "Jack"), First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy ("his widowed bride"),[30] and subsequent killing of his assassin (whose courtroom trial obviously ended as a result ["adjourned"]),[31] the Cuban Missile Crisis ("Jack be nimble, Jack be quick"),[32] the murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner,[33] and elements of culture such as sock hops ("kicking off shoes" to dance, preventing damage to the varnished floor), cruising with a pickup truck,[31][34] the rise of the political protest song ("a voice that came from you and me"), drugs and the counterculture, the Manson Family and the Tate–LaBianca murders in the "summer swelter" of 1969 (the Beatles' song "Helter Skelter") and much more.[6]

Apparent allusions to notable 50s songs include Don Cornell's The Bible Tells Me So ("If the Bible tells you so?"), Marty Robbins' A White Sport Coat, the lonely teenager ("With a pink carnation") mirroring Robbins' narrator who is rejected in favor of another man for the prom, and The Monotones' The Book of Love ("Did you write the book of love").[35]

Many additional and alternative interpretations have also been proposed.

For example, Bob Dylan's first performance in Great Britain was also at a pub called "The King and Queen", and he also appeared more literally "on the sidelines in a (the) cast" – as one of many stars at the back far right of the cover art of the Beatles' album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band ("the Sergeants played a marching tune").[32]

The song title itself is a reference to apple pie, an unofficial symbol of the United States and one of its signature comfort foods,[36] as seen in the popular expression "As American as apple pie".[37] By the twentieth century, this had become a symbol of American prosperity and national pride.[37]

The original United Artists Records inner sleeve featured a free verse poem written by McLean about William Boyd, also known as Hopalong Cassidy, along with a picture of Boyd in full Hopalong regalia. Its inclusion in the album was interpreted to represent a sense of loss of a simplistic type of American culture as symbolized by Hopalong Cassidy and by extension black and white television as a whole.[38]

Mike Mills of R.E.M. reflected: "'American Pie' just made perfect sense to me as a song and that's what impressed me the most. I could say to people this is how to write songs. When you've written at least three songs that can be considered classic that is a very high batting average and if one of those songs happens to be something that a great many people think is one of the greatest songs ever written you've not only hit the top of the mountain but you've stayed high on the mountain for a long time."[39]

McLean's responses

[edit]For McLean, the song is a blueprint of his mind at the time and a homage to his musical influences, but also a roadmap for future students of history:

"If it starts young people thinking about Buddy Holly, about rock 'n' roll and that music, and then it teaches them maybe about what else happened in the country, maybe look at a little history, maybe ask why John Kennedy was shot and who did it, maybe ask why all our leaders were shot in the 1960s and who did it, maybe start to look at war and the stupidity of it — if that can happen, then the song really is serving a wonderful purpose and a positive purpose."

When asked what "American Pie" meant, McLean jokingly replied, "It means I don't ever have to work again if I don't want to."[40] Later, he stated, "You will find many interpretations of my lyrics but none of them by me... Sorry to leave you all on your own like this but long ago I realized that songwriters should make their statements and move on, maintaining a dignified silence."[41] He also commented on the popularity of his music, "I didn't write songs that were just catchy, but with a point of view, or songs about the environment."

In February 2015, however, McLean announced he would reveal the meaning of the lyrics to the song when the original manuscript went for auction in New York City, in April 2015.[42] The lyrics and notes were auctioned on April 7, 2015, and sold for $1.2 million.[43] In the sale catalogue notes, McLean revealed the meaning in the song's lyrics: "Basically in 'American Pie' things are heading in the wrong direction. It [life] is becoming less idyllic. I don't know whether you consider that wrong or right but it is a morality song in a sense."[44] The catalogue confirmed that the song climaxes with a description of the killing of Meredith Hunter at the Altamont Free Concert, ten years after the plane crash that killed Holly, Valens, and Richardson, and did acknowledge that some of the more well-known symbols in the song were inspired by figures such as Elvis Presley ("the king") and Bob Dylan ("the jester").[44]

In 2017, Bob Dylan was asked about how he was referenced in the song. "A jester? Sure, the jester writes songs like 'Masters of War', 'A Hard Rain's a-Gonna Fall', 'It's Alright, Ma' – some jester. I have to think he's talking about somebody else. Ask him."[45]

In 2022, the documentary The Day the Music Died: The Story of Don McLean's American Pie, produced by Spencer Proffer, was released on the Paramount+ video on-demand service. Proffer said that he told McLean: "It's time for you to reveal what 50 years of journalists have wanted to know." McLean stated that he "needed a big song about America", and the first verse and melody ("A long, long time ago...") seemed to just come to mind.[19]

McLean also answered some of the long-standing questions on the song's lyrics, although not all. He revealed that Presley was not the king referenced in the song, Joplin was not the "girl who sang the blues", and Dylan was not the jester, although he is open to other interpretations.[46] He explained that the "marching band" refers to the military–industrial complex, "sweet perfume" refers to tear gas, and Los Angeles is the "coast" that the Trinity head to ("caught the last train for the coast"), commenting "even God has been corrupted". He also said that the line "This'll be the day that I die" originated from the John Wayne film The Searchers (which inspired Buddy Holly's song "That'll Be the Day"), and the chorus's line "Bye-bye, Miss American Pie" was inspired by a song by Pete Seeger, "Bye Bye, My Roseanna". McLean had originally intended to use "Miss American apple pie", but "apple" was dropped.[19]

On the whole, McLean stated that the lyrics were meant to be impressionist, and that many of the lyrics, only a portion of which were included in the finished recording, were completely fictional with no basis in real-life events.[46]

Personnel

[edit]Credits from Richard Buskin, except where noted.[47]

Musicians

[edit]- Don McLean – vocals, acoustic guitar

- Paul Griffin – piano, clavinet[48][49]

- David Spinozza – electric guitar

- Bob Rothstein – bass, backing vocals

- Roy Markowitz – drums

- West Forty Fourth Street Rhythm and Noise Choir – chorus

Technical

[edit]- Ed Freeman - producer

- Tom Flye - engineer, tambourine

- Photography/ artwork – George Whiteman[50]

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

|

Year-end charts[edit]

All-time charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[67] | 5× Platinum | 400,000‡ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[68] | Gold | 45,000‡ |

| Italy (FIMI)[69] | Gold | 50,000‡ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[70] | 4× Platinum | 120,000‡ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[71] | 2× Platinum | 1,200,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[72] | 3× Platinum | 3,000,000‡ |

|

‡ Sales+streaming figures based on certification alone. | ||

Parodies, revisions, and uses

[edit]In 1999, "Weird Al" Yankovic wrote and recorded a parody of "American Pie". Titled "The Saga Begins", the song recounts the plot of Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace from Obi-Wan Kenobi's point of view. While McLean gave permission for the parody, he did not make a cameo appearance in its video, despite popular rumor. McLean himself praised the parody, even admitting to almost singing Yankovic's lyrics during his own live performances because his children played the song so often.[73][74] An unrelated comedy film franchise by Universal Pictures, who secured the rights to McLean's title, also debuted in 1999.[75]

"American Pie" was the last song to be played on Virgin Radio before it was rebranded as Absolute Radio in 2008.[76] It was also the last song played on BFBS Malta in 1979.

Jeremy Renner sings an a cappella version in the 2006 movie Love Comes to the Executioner, as his character walks to the execution chamber.[77]

In 2012, the City of Grand Rapids, Michigan, created a lip dub video to "American Pie" in response to a Newsweek article that stated the city was "dying".[78] (Due to licensing issues, the version used in the video was not the original, but rather a later-recorded live version.) The video was hailed as a fantastic performance by many, including film critic Roger Ebert, who said it was "the greatest music video ever made".[79]

On March 21, 2013, Harmonix announced that "American Pie" would be the final downloadable track made available for the Rock Band series of music video games.[80] This was the case until Rock Band 4 was released on October 6, 2015, reviving the series' weekly releases of DLC.

On March 14, 2015, the National Museum of Mathematics announced that one of two winners of its songwriting contest was "American Pi" by mathematics education professor Dr. Lawrence M. Lesser.[81] The contest was in honor of "Pi Day of the Century" because "3/14/15" would be the only day in the 21st-century showing the first five digits of π (pi).

On April 20, 2015, John Mayer covered "American Pie" live on the Late Show with David Letterman, at the request of the show's eponymous host.[82]

On January 29, 2021, McLean released a re-recording of "American Pie" featuring lead vocals by country a cappella group Home Free.[83]

The song was featured in Marvel's Black Widow movie in 2021.[84] It is the favorite song of the character Yelena Belova, and sung by Red Guardian later in the film to comfort her.[85]

"American Pie" is also featured in the 2021 Tom Hanks movie Finch.[86]

During his visit to the United States in 2023, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol sang this song at a state dinner.[87] This has attracted worldwide attention, as well as the attention of Don McLean. [88]

Madonna version

[edit]| "American Pie" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Madonna | ||||

| from the album The Next Best Thing | ||||

| Released | February 8, 2000 | |||

| Recorded | September 1999 | |||

| Studio | Undisclosed location (New York City) | |||

| Genre | Dance-pop | |||

| Length | 4:33 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Songwriter(s) | Don McLean | |||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| Madonna singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "American Pie" on YouTube | ||||

Background and release

[edit]American singer Madonna recorded a cover version of "American Pie" for the soundtrack of her film The Next Best Thing (2000). Her cover is much shorter than the original, containing only the beginning of the first verse and all of the second and sixth verses. Reworked as a dance-pop track, it was produced by Madonna and William Orbit. It was recorded in September 1999 in New York City, after Rupert Everett, Madonna's co-star in The Next Best Thing, convinced her to cover the song for the film's soundtrack.[89][90] Madonna said of her choice to cover the song: "To me, it's a real millennium song. We're going through a big change in terms of the way we view pop culture, because of the Internet. In a way, it's like saying goodbye to music as we knew it—and to pop culture as we knew it."[91] "American Pie" was released as the lead single from The Next Best Thing on February 8, 2000, by Maverick Records and Warner Bros. Records.[92]

"American Pie" was later included as an international bonus track on her eighth studio album, Music (2000). However, it was not included on her greatest hits compilation GHV2 (2001), as Madonna had regretted putting it on Music, elaborating: "It was something a certain record company executive twisted my arm into doing, but it didn't belong on the album so now it's being punished... My gut told me not to [put the song on Music], but I did it and then I regretted it so just for that reason it didn't deserve a place on GHV2".[93][94] A remix of the song was featured on her remix compilation album Finally Enough Love: 50 Number Ones (2022).

Reception

[edit]"American Pie" was an international hit, reaching number one in numerous countries, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Iceland, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Austria and Finland. The song was the 19th-best-selling single of 2000 in the UK and the ninth best-selling single of 2000 in Sweden. The single was not released commercially in the United States, but it reached number 29 on the Billboard Hot 100 due to strong radio airplay.

Chuck Taylor of Billboard was impressed by the recording and commented, "Applause to Madonna for not pandering to today's temporary trends and for challenging programmers to broaden their playlists. ... In all, a fine preview of the forthcoming soundtrack to The Next Best Thing."[95] Peter Robinson of The Guardian called the cover as "brilliant".[96] Don McLean himself praised the cover, saying it was "a gift from a goddess", and that her version is "mystical and sensual".[97] NME, on the other hand, gave it a negative review, saying that "Killdozer did it first and did it better", that it was "sub-karaoke fluff" and that "it's a blessing she didn't bother recording the whole thing."[98]

In 2017, the Official Charts Company stated the song had sold 400,000 copies in the United Kingdom and was her 16th best selling single to date in the nation.[99]

Music video

[edit]The music video, filmed in the southern United States and in London,[100] and directed by Philipp Stölzl, depicts a diverse array of ordinary Americans, including scenes showing same-sex couples kissing. Throughout the music video Madonna, who is wearing a tiara on her head, dances and sings in front of a large American flag.[101]

Two versions of the video were produced, the first of which was released as the official video worldwide, and later appeared on Madonna's Celebration: The Video Collection (2009). The second version used the "Humpty Remix", a more upbeat and dance-friendly version of the song. The latter aired on MTV in the US to promote The Next Best Thing; it features different footage and new outtakes of the original while omitting the lesbian kiss. Everett, who provides backing vocals in the song, is also featured in the video.

Formats and track listings

[edit]

|

|

Credits and personnel

[edit]Credits are adapted from the liner notes for "American Pie".[112]

- Madonna – vocals, production

- William Orbit – production, guitar, drums, keyboard

- Don McLean – songwriting

- Mark "Spike" Stent – mixing

- Rupert Everett – backing vocals

- Mark Endert – engineering

- Sean Spuehler – engineering, programming

- Jake Davies – engineering

- Rico Conning – sequencer programming

- Dah Len – photography

Charts

[edit]

Weekly charts[edit] |

Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[170] | Gold | 35,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[171] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Belgium (BEA)[172] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Denmark | — | 12,701[173] |

| France (SNEP)[174] | Gold | 250,000* |

| Germany (BVMI)[175] | Gold | 250,000^ |

| Italy | — | 70,000[176] |

| Spain | — | 35,000[177] |

| Sweden (GLF)[178] | Platinum | 30,000^ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[179] | Gold | 25,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[180] | Gold | 400,000[99] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Release history

[edit]| Region | Date | Format(s) | Label(s) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | February 8, 2000 | Contemporary hit radio | ||

| France | February 25, 2000 | Maverick | ||

| Germany | February 28, 2000 | Maxi CD | Warner Music | |

| United Kingdom |

|

|||

| Australia | March 7, 2000 | Maxi CD[a] | Warner Music | |

| Japan | March 8, 2000 | Maxi CD |

Notes

[edit]See also

[edit]- Vincent (Don McLean song)

- List of Australian chart achievements and milestones

- List of Romanian Top 100 number ones of the 2000s

- List of best-selling singles by year (Germany)

References

[edit]- ^ DeMain, Bill (August 18, 2021). "The story behind American Pie by Don McLean". Loudersound.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2021.

- ^ "The Hot 100 Week of January 15, 1972". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "The Hot 100 Week of November 27, 1971". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ "The Longest & Shortest Hot 100 Hits: From Kendrick Lamar, Beyoncé & David Bowie to Piko-Taro". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ Trust, Gary (November 22, 2021). "Taylor Swift's 'All Too Well (Taylor's Version)' Soars In at No. 1 on Billboard Hot 100". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved November 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Don McLean explains why he won't reveal the meaning of "American Pie"". CBS News. March 29, 2017. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

"But the quartet practicing in the park, that's not the Beatles?" Axelrod asked. "No," McLean replied.

- ^ a b c "Decoding the Ambiguous Lyrics of Don McLean's American Pie". Musicoholics. July 26, 2020. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Understanding American Pie – Interpretation of Don Mclean's epic anthem to the passing of an era". UnderstandingAmericanPie.com. Archived from the original on September 6, 2003. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ The Day the Music Died: A Closer Look at the Lyrics of "American Pie" Archived June 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine: States "I met a girl who sang the blues/And I asked her for some happy news/But she just smiled and turned away – McLean turns to Janis Joplin for hope, but she dies of a heroin overdose on October 4, 1970."

- ^ Songfacts: American Pie Archived June 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine: States that "The line, 'I met a girl who sang the blues and I asked her for some happy news, but she just smiled and turned away,' is probably about Janis Joplin. She died of a drug overdose in 1970."

- ^ "National Recording Registry Picks Are 'Over the Rainbow'". Library of Congress. March 29, 2017. Archived from the original on March 29, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ^ "Don McLean sets 'American Pie' 50th anniversary Europe/UK tour". AM 880 KIXI. September 21, 2021. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ Cott, Jonathan (February 5, 2009). "The Last Days of Buddy Holly". Rolling Stone. No. 1071. Archived from the original on April 7, 2023. Retrieved May 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c "'American Pie' Still Homemade, but With a New Twist". The New York Times. November 30, 2011. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Release: Don Mclean's Original Manuscript For "American Pie" To Be Sold At Christie's New York, 7 April 2015". Christie's. February 13, 2015. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "Memory Bank's a Little Off, But Sentiment Still Holds". Philly. August 12, 2012. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "The Day The Music Died: American Pie – Watch Movie Trailer", Paramount Plus, archived from the original on October 5, 2022, retrieved July 29, 2022

- ^ McDonald, Shannon (November 28, 2011). "Don McLean: 'American Pie' was written in Philly and first performed at Saint Joseph's University". Newsworks. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy, Mark (July 20, 2022). "Don McLean looks back at his masterpiece, 'American Pie'". AP. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Coen, Jim (April 23, 2015). "Don McLean Revisits His Tasty Classic, "American Pie"". Guitar World. Archived from the original on September 3, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ Schuck & Schuck 2012, p. 15.

- ^ "Cashbox Single Picks" (PDF). Cash Box. November 20, 1971. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ "Picks of the Week" (PDF). Record World. November 20, 1971. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ ""American Pie" – Don McLean". Super seventies. Archived from the original on June 22, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Browne, Ray Broadus; Ambrosetti, Ronald J. (May 11, 1993). Continuities in Popular Culture: The Present in the Past & the Past in the Present and Future. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-593-8. Archived from the original on November 29, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ "American Pie". Don-McLean.com. p. 68. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ McLean, Don (February 1, 2009). "Commentary: Buddy Holly, rock music genius". CNN. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Maslin, Janet in Miller, Jim (ed.) (1981), The Rolling Stone History of Rock & Roll, p. 220

- ^ "Murder at the Altamont Festival brings the 1960s to a violent end". History.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "Gloomy Don McLean reveals meaning of 'American Pie'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 9, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

- ^ a b ""American Pie" Lyrics – What Do They Mean?". WHRC WI. Archived from the original on July 17, 2021. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Barrell, Tony (March 26, 2015). "The American pie enigma". Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ O'Brien, P. (March 3, 1999). "Understanding the lyrics of American Pie: The analysis and interpretation of Don McLean's song lyrics". The Octopus's Garden. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ "American Pie". Edlis. Archived from the original on April 14, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ Shuck, Raymond (2012). Do You Believe in Rock and Roll?: Essays on Don McLean's "American Pie". McFarland & Company. pp. 55, 56 & 57. ISBN 978-0-786-47105-8.

- ^ D'Aiutolo, Olivia (August 17, 2015). "A Pinch of History: Amelia Simmons's Apple Pie". Fondly, Pennsylvania. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Cambridge University Press (2011). "Definition of "as American as apple pie"". Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary & Thesaurus. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Fann, James M. (December 10, 2006). "Understanding AMERICAN PIE". Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ Don McLean: An American Troubadour (Television production). UK: Sky Arts 1. 2013.

- ^ Howard, Dr. Alan. "The Don McLean Story: 1970–1976". Don-McLean.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved June 3, 2007.

- ^ "What is Don McLean's song "American Pie" all about?". The Straight Dope. May 14, 1993. Archived from the original on May 28, 2007. Retrieved June 3, 2007.

- ^ "Don McLean to reveal meaning of American Pie lyrics". BBC News. February 13, 2015. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "American Pie lyrics sell for $1.2m". BBC News. April 7, 2015. Archived from the original on August 20, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ^ a b Hawksley, Rupert (April 7, 2015). "American Pie: 6 crazy conspiracy theories". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022.

- ^ "Bob Dylan's Surprise New Interview: 9 Things We Learned". Rolling Stone. March 23, 2017. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ^ a b Farber, Jim (July 19, 2022). "'I said, Don, it's time for you to reveal': 50 years later, the truth behind American Pie". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ^ Buskin, Richard. "Classic Tracks: Don McLean 'American Pie'". Sound On Sound. Retrieved July 12, 2023.

- ^ Hasted, Nick (April 7, 2015). "The Making Of... Don McLean's "American Pie"". uncut.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 1, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- ^ Hepworth, Paul (2016). 1971 - Never a Dull Moment: Rock's Best Year. Bantam Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-059307486-2.

- ^ "Don McLean - American Pie (1971) | Classic Album Art". Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ a b Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (doc). Australian Chart Book, St Ives, N.S.W. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Don McLean – American Pie" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 5302." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "Top RPM Adult Contemporary: Issue 5343." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – American Pie". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ "NZ Listener chart statistics for American Pie". flavourofnz.co.nz. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ "Don McLean – American Pie". VG-lista. Retrieved December 19, 2015.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "Don McLean: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Don McLean Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Don McLean Chart History (Adult Contemporary)". Billboard. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Don McLean – American Pie" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved November 15, 2017. To see peak chart position, click "TITEL VON Don McLean"

- ^ "RPM Top Singles of 1972". RPM. Vol. 18, no. 21, 22. January 13, 1973. p. 20.

- ^ "Top Selling Singles for 1972". Sounds. London, England: Spotlight Publications. January 1973.

- ^ "Billboard Top 100 – 1972". Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ "Billboard Hot 100 60th Anniversary Interactive Chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ "Canadian single certifications – Don McLean – American Pie". Music Canada. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ "Danish single certifications – Don McLean – American Pie". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ "Italian single certifications – Don McLean – American Pie" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ "New Zealand single certifications – Don McLean – American Pie". Radioscope. Retrieved December 21, 2024. Type American Pie in the "Search:" field.

- ^ "British single certifications – Don McLean – American Pie". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ "American single certifications – Don McLean – American Pie". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ ""Ask Al" Q&As for September, 1999". Archived from the original on September 2, 2006. Retrieved October 29, 2006.

- ^ "Jedi Council – Interviews Weird Al Yankovic". TheForce.Net. September 14, 1980. Archived from the original on October 22, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ Parish, James Robert (June 2000). Jason Biggs: Hollywood's Newest Cutie-Pie!. Macmillan Publishers. pp. 3, 5, 126. ISBN 0-312-97622-4. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ "Mixcloud". Mixcloud. Archived from the original on July 10, 2021. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "Love Comes to the Executioner". IMDb.

- ^ "The Grand Rapids Lip Dub". NPR. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "The greatest music video ever made". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 2, 2011.

- ^ "Rock Band's final song will be Don McLean's 'American Pie'". Polygon. March 21, 2013. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ "2015 Pi Day Contest Winners". National Museum of Mathematics. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015. Retrieved April 8, 2015.

- ^ "John Mayer covers 'American Pie' for David Letterman". theweek.com. April 20, 2015. Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2020.

- ^ "Don McLean releases new a cappella version of "American Pie" featuring country vocal group Home Free". abcnewsradioonline.com. January 29, 2021. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "David Harbour says it was his idea to use the song 'American Pie' in 'Black Widow' because his big scene with Florence Pugh needed to be 'more profound'". news.yahoo.com. July 10, 2021. Archived from the original on July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ "David Harbour Explains the Significance of American Pie in Black Widow". ScreenRant. July 12, 2021. Archived from the original on August 5, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Anderson, John (November 3, 2021). "'Finch' Review: Man's Best Friends". WSJ. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2021.

- ^ "'I had no damn idea you could sing': Yoon's 'American Pie' stuns Biden". AFP. April 27, 2023. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Don McLean offers duet with South Korean president who sang'American Pie'to Biden". CNN. April 27, 2023. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ^ Kaufman, Gil (September 24, 1999). "Madonna and William Orbit take another spin in studio". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 2, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "Madonna's piece of American Pie". BBC News. February 3, 2000. Archived from the original on May 5, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ Farber, Jim (February 27, 2000). "Mellow Madonna: the star reflects on playing a loser in love in 'The Next Best Thing'". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on December 10, 2022. Retrieved December 10, 2022.

- ^ a b "Going For Adds" (PDF). Radio & Records. No. 1336. February 4, 2000. p. 39. Retrieved December 5, 2024 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "Jo Whiley Interviews Madonna". BBC Radio 1. November 23, 2001. Archived from the original on December 5, 2001. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- ^ "Madonna rejected 'American Pie' for GHV2". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. November 23, 2001. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Taylor, Chuck (February 12, 2000). "Spotlight: Madonna "American Pie"". Billboard. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ Robinson, Peter (August 15, 2008). "Madonna: 50 poptastic facts". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 6, 2022. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ^ "Don McLean Praises Madonna's 'American Pie'". MTV. February 2, 2000. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ^ "NME Track Reviews – American Pie". NME. February 26, 2000. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Copsey, Rob (March 9, 2017). "Flashback: Madonna scored her 9th UK Number 1 single with American Pie 17 years ago this week". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on March 11, 2017. Retrieved March 9, 2017.

- ^ Ciccone, Christopher (2008) Life with my Sister Madonna, Simon & Schuster: New York, p.278.

- ^ Richin, Leslie (March 3, 2015). "Madonna Covered Don McLean's 'American Pie' 17 Years Ago Today". Billboard. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (2-track CD single). Warner Music Group. 5439-16879-2.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (CD maxi-single). Warner Music Group. 9362-44837-2.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (CD maxi-single). Warner Music Group. 9362-44839-2.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (maxi CD single). Warner Music Japan. WPCR-10693.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (CD maxi-single). Warner Music Group. 9362-44840-2.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (CD maxi-single). Warner Music Group. 9362-44864-2.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (CD maxi-single). Warner Music Group. WPCR-10693.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (12-inch vinyl). Warner Music Group. 9362-44865-0.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (12-inch vinyl). Warner Music Group. 9362-44865-0.

- ^ "American Pie - Single by Madonna on Apple Music". Apple Music. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ Madonna (2000). American Pie (Liner notes). Maverick Records. 9362448372.

- ^ a b "Madonna – American Pie". ARIA Top 50 Singles. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie" (in French). Ultratop 50. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Hits of the World: Canada". Billboard. March 18, 2000. p. 52. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 9756." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Top RPM Adult Contemporary: Issue 9764." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Top RPM Dance/Urban: Issue 9729." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "HR Top 20 Lista". Croatian Radiotelevision. Archived from the original on May 10, 2000. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ "Hitparada radia 2000" (in Czech). International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on June 13, 2000. Retrieved July 21, 2020. See Nejvys column.

- ^ a b "Top National Sellers" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 17, no. 13. March 25, 2000. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "Eurochart Hot 100 Singles" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 17, no. 12. March 18, 2000. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Madonna: American Pie" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Top National Sellers" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 17, no. 14. April 1, 2000. p. 13. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

- ^ "Íslenski Listinn Topp 40 (Vikuna 30.3. – 6.4. 2000)". Dagblaðið Vísir (in Icelandic). March 31, 2000. p. 12. Archived from the original on July 21, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – American Pie". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie". Top Digital Download. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "マドンナのシングル売り上げランキング" [Madonna's Single Sales Chart] (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – Madonna" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie". VG-lista. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Los Discos Más Vendicos En Iberoamérica y Estados Unidos". El Siglo de Torreón (in Spanish). May 29, 2000. Archived from the original on March 17, 2022. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Romanian Top 100: Top of the Year 2000" (in Romanian). Romanian Top 100. Archived from the original on January 22, 2005.

- ^ "Official Scottish Singles Sales Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie" Canciones Top 50. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie". Singles Top 100. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna – American Pie". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Madonna Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna Chart History (Adult Contemporary)". Billboard. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna Chart History (Adult Pop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna Chart History (Dance Club Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "Madonna Chart History (Pop Songs)". Billboard. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "ARIA Top 100 Singles for 2000". ARIA. Archived from the original on January 5, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Jahreshitparade Singles 2000" (in German). Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 2000". Ultratop (in Dutch). Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ "Rapports annuels 2000". Ultratop (in French). Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ "Års Hitlister 2000: IFPI Danmark: Singles top 50" (in Danish). IFPI Danmark. 2000. Archived from the original on November 16, 2001. Retrieved April 8, 2021 – via Musik.org.

- ^ "Year in Focus – Eurochart Hot 100 Singles 2000" (PDF). Music & Media. Vol. 17, no. 52. December 23, 2000. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ "Tops de L'année | Top Singles 2000" (in French). SNEP. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 Single–Jahrescharts 2000" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Archived from the original on May 9, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

- ^ "Íslenski Listinn Topp 100". Dagblaðið Vísir (in Icelandic). January 5, 2001. p. 10. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 of 2000". Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Archived from the original on June 2, 2004. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ "Top 100–Jaaroverzicht van 2000". Dutch Top 40. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Single 2000" (in Dutch). Archived from the original on January 29, 2012. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- ^ "Topp 20 Single Vår 2000" (in Norwegian). VG-lista. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Sociedad General de Autores y Editores (SGAE) (2001). "Anuario 2000: CD-Singles Más Vendidos en 2000". Anuarios SGAE (in Spanish): 228. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "Årslista Singlar, 2000" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Swiss Year-End Charts 2000" (in German). Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ "Yearly Best Selling Singles" (PDF). British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ a b "Airplay Monitor: The Best of 2000" (PDF). Billboard. December 22, 2000. pp. 48, 54. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ "The Year in Music 2000: Hot Dance Club-Play Singles" (PDF). Billboard. December 30, 2000. p. YE-59. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Singles of 2001". Jam!. Archived from the original on January 26, 2003. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ "Canada's Top 200 Singles of 2002 (Part 2)". Jam!. January 14, 2003. Archived from the original on September 6, 2004.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2000 Singles" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ "Austrian single certifications – Madonna – American Pie" (in German). IFPI Austria. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop − Goud en Platina – singles 2000". Ultratop. Hung Medien. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ "Hitlist 2000". Hitlisten. IFPI Denmark. Archived from the original on December 20, 2002. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "French single certifications – Madonna – American Pie" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique. Retrieved August 19, 2022.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Madonna; 'American Pie')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ Dondoni, Luca (July 27, 2000). "Madonna si lancia nello spazio". La Stampa (in Italian) (203): 25. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

«American Pie» che come singolo presente nella colonna sonora del film «The next big thing» solo nel nostro paese ha venduto ben 70 mila copie

- ^ "La mejor musica de la pantalla". La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). March 14, 2000. p. 75. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2021 – via Biblioteca Nacional de España.

En España ha vendido 35.000 copias en dos semanas a pesar de que la cinta aún no se ha estrenado

- ^ "Guld- och Platinacertifikat − År 2000" (PDF) (in Swedish). IFPI Sweden. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 17, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('American Pie')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- ^ "British single certifications – Madonna – American Pie". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "American pie" (in French). Maverick Records. February 25, 2000. Retrieved December 5, 2024 – via Fnac.

- ^ "American pie" (in French). Maverick Records. February 25, 2000. Retrieved December 5, 2024 – via Fnac.

- ^ "American Pie" (in German). Warner Music Group. February 28, 2000. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved December 5, 2024 – via Amazon.

- ^ "New Releases – For Week Starting 28 February, 2000" (PDF). Music Week. February 26, 2000. p. 27. Retrieved December 5, 2024 – via World Radio History.

- ^ "アメリカン・パイ" [American Pie] (in Japanese). Warner Music Japan. March 8, 2000. Retrieved December 5, 2024 – via Oricon.

Further reading

[edit]- Adams, Cecil (May 15, 1993). "What is Don McLean's song 'American Pie' all about?". The Straight Dope. Chicago Reader, Inc. Retrieved June 8, 2009. An interpretation of the lyrics based on a supposed interview of McLean by DJ Casey Kasem. McLean later confirmed the Buddy Holly reference in a letter to Adams but denied ever speaking to Kasem.

- Roteman, Jeff (August 10, 2002). "Bob Dearborn's Original Analysis of Don McLean's 1971 Classic 'American Pie'". This article correlates McLean's biography with the historic events in the song. McLean pointed to WCFL (Chicago, Illinois) radio disc jockey Bob Dearborn as the partial basis for most mainstream interpretations of "American Pie". Dearborn's analysis, mailed to listeners on request, bears the date January 7, 1972. Roteman's reprinting added photos but replaced the date January 7, 1972, by an audio link bearing the date February 28, 1972, the date Dearborn aired his interpretation on WCFL (http://user.pa.net/~ejjeff/bobpie.ram (Bob Dearborn's American Pie Analysis original broadcast February 28, 1972)).

- "The WCFL Radio Tribute Page". Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018. Among the potpourri is a copy of the January 7, 1972, Bob Dearborn letter, plus an audio recording, in which he delineates his interpretation of "American Pie".

- Fann, Jim. "Understanding American Pie". Archived from the original on September 6, 2003. Historically oriented interpretation of "American Pie". The interpretation was specifically noted on in an archived version of McLean's website page on "American Pie".archived version of McLean's website page on "American Pie". The material, dated November 2002, includes a recording of Dinah Shore singing "See The USA In Your Chevrolet" and a photograph of Mick Jagger in costume at the Altamont Free Concert with a Hells Angel member in the background.

- Full "See the US in Your Chevrolet" lyrics for Dinah Shore on "The Dinah Shore Chevy Show" (1956–1961)

- Kulawiec, Rich (August 26, 2001). "FAQ: The Annotated 'American Pie'". Archived from the original on April 19, 2003. Retrieved September 19, 2007. FAQ maintained by Rich Kulawiec, started in 1992 and essentially completed in 1997.

- "American Pie—A Rock Epic" A multi-media presentation of Rich Kulawiec's The Annotated "American Pie".

- Levitt, Saul (May 26, 1971). "Interpretation of American Pie – analysis, news, Don McLean, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, Rock & Roll". Missamericanpie.co.uk. Archived from the original on April 5, 2011. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- Schuck, Raymond I.; Schuck, Ray (2012). Do You Believe in Rock and Roll?: Essays on Don McLean's "American Pie". McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-7105-8. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

External links

[edit]- The Official Website of Don McLean and American Pie provides the songwriter's own biography, lyrics and clues to the song's meaning.

- Don McLean - American Pie (Part 1) on YouTube

- 1970s ballads

- 1971 singles

- 1971 songs

- 2000 singles

- Billboard Hot 100 number-one singles

- Cashbox number-one singles

- Cultural depictions of Buddy Holly

- Don McLean songs

- European Hot 100 Singles number-one singles

- Folk ballads

- Grammy Hall of Fame Award recipients

- Irish Singles Chart number-one singles

- Madonna songs

- Maverick Records singles

- Number-one singles in Australia

- Number-one singles in the Czech Republic

- Number-one singles in Finland

- Number-one singles in Iceland

- Number-one singles in Italy

- Number-one singles in Germany

- Number-one singles in Hungary

- Number-one singles in New Zealand

- Number-one singles in Romania

- Number-one singles in Scotland

- Number-one singles in Spain

- Number-one singles in Sweden

- Number-one singles in Switzerland

- Rock ballads

- RPM Top Singles number-one singles

- Song recordings produced by Madonna

- Song recordings produced by William Orbit

- Songs about Buddy Holly

- Songs about rock music

- Songs about nostalgia

- Songs based on American history

- Songs inspired by deaths

- Songs written by Don McLean

- UK singles chart number-one singles

- United Artists Records singles

- United States National Recording Registry recordings

- Warner Records singles

- Commemoration songs