Gabon

Gabonese Republic République gabonaise (French) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Union, Travail, Justice" (French) "Union, Work, Justice" | |

| Anthem: "La Concorde" (French) "The Concord" | |

| Capital and largest city | Libreville 0°23′N 9°27′E / 0.383°N 9.450°E |

| Official languages | French |

| Regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Unitary presidential republic under a military junta[2] |

| Brice Oligui Nguema | |

| Joseph Owondault Berre | |

| Raymond Ndong Sima | |

| Legislature | Parliament of Gabon (suspended) |

| Independence from | |

• Republic established | 28 November 1958 |

• Granted | 17 August 1960 |

| 30 August 2023 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 267,668 km2 (103,347 sq mi) (76th) |

• Water (%) | 3.76% |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 2,397,368[6] (146th) |

• Density | 7.9/km2 (20.5/sq mi) (216th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2017) | 38[8] medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | medium (123rd) |

| Currency | Central African CFA franc (XAF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Drives on | right |

| Calling code | +241 |

| ISO 3166 code | GA |

| Internet TLD | .ga |

Gabon (/ɡəˈbɒn/ gə-BON; French pronunciation: [ɡabɔ̃] ), officially the Gabonese Republic (French: République gabonaise), is a country on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa, on the equator, bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north, the Republic of the Congo on the east and south, and the Gulf of Guinea to the west. It has an area of 270,000 square kilometres (100,000 sq mi) and a population of 2.3 million people. There are coastal plains, mountains (the Cristal Mountains and the Chaillu Massif in the centre), and a savanna in the east. Libreville is the country's capital and largest city.

Gabon's original inhabitants were the pygmy peoples. Beginning in the 14th century, Bantu migrants began settling in the area as well. The Kingdom of Orungu was established around 1700. The region was colonised by France in the late 19th century. Since its independence from France in 1960, Gabon has had three presidents. In the 1990s, it introduced a multi-party system and a democratic constitution that aimed for a more transparent electoral process and reformed some governmental institutions. Despite this, the Gabonese Democratic Party (PDG) remained the dominant party until its removal from the 2023 Gabonese coup d'état.

Gabon is a developing country, ranking 123rd in the Human Development Index. It is one of the wealthiest countries in Africa in terms of per capita income; however, large parts of the population are very poor. Omar Bongo came to office in 1967 and created a dynasty, which stabilized its power through a clientist network, Françafrique.[10]

The official language of Gabon is French, and Bantu ethnic groups constitute around 95% of the country's population. Christianity is the nation's predominant religion, practised by about 80% of the population. With petroleum and foreign private investment, it has the fourth highest HDI[11] (after Mauritius, Seychelles, and South Africa) and the fifth highest GDP per capita (PPP) (after Seychelles, Mauritius, Equatorial Guinea, and Botswana) of any African nation. Gabon's nominal GDP per capita is $10,149 in 2023 according to OPEC.[12]

History

[edit]Pre-colonisation

[edit]Pygmy peoples in the area were largely replaced and absorbed by Bantu tribes as they migrated. By the 18th century, a Myeni-speaking kingdom known as the Kingdom of Orungu formed as a trading centre with the ability to purchase and sell slaves, and fell with the demise of the slave trade in the 1870s.[13]

French rule and independence

[edit]Explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza led his first mission to the Gabon-Congo area in 1875.[14] He founded the town of Franceville and was later colonial governor. Some Bantu groups lived in the area when France officially occupied it in 1885.

In 1910, Gabon became a territory of French Equatorial Africa,[15] a federation that survived until 1958. In World War II, the Allies invaded Gabon in order to overthrow the pro-Vichy France colonial administration. On 28 November 1958, Gabon became an autonomous republic within the French Community, and on 17 August 1960, it became fully independent.[16]

Independence

[edit]M'ba rule

[edit]The first president of Gabon, elected in 1961, was Léon M'ba, with Omar Bongo Ondimba as his vice president. After M'ba's accession to power, the press was suppressed, political demonstrations suppressed, freedom of expression curtailed, other political parties gradually excluded from power, and the Constitution changed along French lines to vest power in the Presidency, a post that M'ba assumed himself. When M'ba dissolved the National Assembly in January 1964 to institute one-party rule, an army coup sought to oust him from power and restore parliamentary democracy. French paratroopers flew in within 24 hours to restore M'ba to power. After days of fighting, the coup ended and the opposition was imprisoned, with protests and riots.

Bongo rule and PDG

[edit]When M'Ba died in 1967, Bongo replaced him as president. In March 1968, Bongo declared Gabon a 1-party state by dissolving BDG and establishing a new party – the Parti Démocratique Gabonais (PDG). He invited all Gabonese, regardless of previous political affiliation, to participate. Bongo sought to forge a single national movement in support of the government's development policies, using PDG as a tool to submerge the regional and tribal rivalries that had divided Gabonese politics in the past. Bongo was elected president in February 1975; in April 1975, the position of vice president was abolished and replaced by the position of prime minister, who had no right to automatic succession. Bongo was re-elected President in December 1979 and November 1986 to 7-year terms.[17]

In 1990, economic discontent and a desire for political liberalization provoked demonstrations and strikes by students and workers. In response to grievances by workers, Bongo negotiated with them on a sector-by-sector basis, making wage concessions. He promised to open up PDG and to organize a national political conference in March–April 1990 to discuss Gabon's future political system. PDG and 74 political organizations attended the conference. Participants essentially divided into 2 "loose" coalitions, ruling PDG and its allies, and the United Front of Opposition Associations and Parties, consisting of the breakaway Morena Fundamental and the Gabonese Progress Party.[17]

Transitional government and RSDG

[edit]The April 1990 conference approved political reforms, including creation of a national Senate, decentralization of the budgetary process, freedom of assembly and press, and cancellation of an exit visa requirement. In an attempt to guide the political system's transformation to multiparty democracy, Bongo resigned as PDG chairman and created a transitional government headed by a new Prime Minister, Casimir Oye-Mba. The Gabonese Social Democratic Grouping (RSDG), as the resulting government was called, was smaller than the previous government and included representatives from some opposition parties in its cabinet. RSDG drafted a provisional constitution in May 1990 that provided a basic bill of rights and an independent judiciary and retained "strong" executive powers for the president. After further review by a constitutional committee and the National Assembly, this document came into force in March 1991.[17]

Opposition to PDG continued after the April 1990 conference, and in September 1990, two coup d'état attempts were uncovered and aborted. With demonstrations after the death of an opposition leader, the first multiparty National Assembly elections in almost 30 years took place in September–October 1990, with PDG garnering a majority.[17]

Bongo's re-election and rule

[edit]

Following President Omar Bongo's re-election in December 1993 with 51% of the vote, opposition candidates refused to validate the election results. Civil disturbances and violent repression led to an agreement between the government and opposition factions to work toward a political settlement. These talks led to the Paris Accords in November 1994, under which some opposition figures were included in a government of national unity. This arrangement broke down and the 1996 and 1997 legislative and municipal elections provided the background for renewed partisan politics. PDG won in the legislative election, and some cities, including Libreville, elected opposition mayors during the 1997 local election.[17]

Boycott of elections and crisis

[edit]Facing a divided opposition, President Omar Bongo coasted to re-election in December 1998. While some of Bongo's opponents rejected the outcome as fraudulent, some international observers characterized the results as representative "despite many perceived irregularities". Legislative elections held in 2001–2002 were boycotted by a number of smaller opposition parties and were criticized for their administrative weaknesses, produced a National Assembly dominated by PDG and allied independents. In November 2005 President Omar Bongo was elected for his sixth term. He won re-election, and opponents claim that the balloting process was marred by irregularities. There were some instances of violence following the announcement of his win.[17] National Assembly elections were held in December 2006. Some seats contested because of voting irregularities were overturned by the Constitutional Court, and the subsequent run-off elections in 2007 yielded a PDG-controlled National Assembly.[17]

Death of Bongo and succession

[edit]

Following the death of President Omar Bongo on 8 June 2009 due to cardiac arrest at a Spanish hospital in Barcelona, Gabon entered a period of political transition. Per the amended constitution, Rose Francine Rogombé, the President of the Senate, assumed the role of Interim President on 10 June 2009. The subsequent presidential elections, held on 30 August 2009, marked a historic moment as they were the first in Gabon's history not to feature Omar Bongo as a candidate. With a crowded field of 18 contenders, including Omar Bongo's son and ruling party leader, Ali Bongo, the elections were closely watched both domestically and internationally.

After a rigorous three-week review by the Constitutional Court, Ali Bongo was officially declared the winner, leading to his inauguration on 16 October 2009.[17] However, the announcement of his victory was met with skepticism by some opposition candidates, sparking sporadic protests across the country. Nowhere was this discontent more pronounced than in Port-Gentil, where allegations of electoral fraud resulted in violent demonstrations. The unrest claimed four lives and led to significant property damage, including attacks on the French Consulate and a local prison. Subsequently, security forces were deployed, and a curfew remained in effect for over three months.[17]

In June 2010, a partial legislative by-election was held, marking the emergence of the Union Nationale (UN) coalition, primarily comprising defectors from the ruling PDG party following Omar Bongo's death. The contest for the five available seats saw both the PDG and UN claiming victory, underscoring the political tensions that persisted in the aftermath of the presidential transition.[17]

The political landscape was further disrupted in January 2019 when a group of soldiers attempted a coup against President Ali Bongo. Despite initial unrest, the coup ultimately failed, but it highlighted the ongoing challenges facing Gabon's political stability.[18]

Against this backdrop of political volatility, Gabon achieved significant milestones on the international stage. In June 2021, it became the first country to receive payments for reducing emissions resulting from deforestation and forest degradation. Additionally, in June 2022, Gabon, along with Togo, joined the Commonwealth of Nations, signalling its commitment to multilateral engagement and cooperation.[19]

2023 coup d'état

[edit]In August 2023, following the announcement that Ali Bongo had won a third term in the general election, military officers announced that they had taken power in a coup d'état and cancelled the election results. They also dissolved state institutions including the Judiciary, Parliament and the constitutional assembly.[20][21] On 31 August 2023, army officers who seized power, ending the Bongo family's 55-year hold on power, named Gen Brice Oligui Nguema as the country's transitional leader.[22] On 4 September 2023, General Nguema was sworn in as interim president of Gabon.[23]

In November 2024, a referendum on a new constitution was approved, reforming the country's government.[24]

Politics

[edit]The presidential republic form of government is stated under the 1961 constitution (revised in 1975, rewritten in 1991, and revised in 2003). The president is elected by universal suffrage for a seven-year term; a 2003 constitutional amendment removed presidential term limits. The president can appoint and dismiss the prime minister, the cabinet, and judges of the independent Supreme Court. The president has other powers such as authority to dissolve the National Assembly, declare a state of siege, delay legislation, and conduct referendums.[17] Gabon has a bicameral legislature with a National Assembly and Senate. The National Assembly has 120 deputies who are popularly elected for a five-year term. The Senate is composed of 102 members who are elected by municipal councils and regional assemblies and serve for six years. The Senate was created in the 1990–1991 constitutional revision, and was not brought into being until after the 1997 local elections. The President of the Senate is next in succession to the President.[17]

In 1990, the government made changes to Gabon's political system. A transitional constitution was drafted in May 1990 as an outgrowth of the national political conference in March–April and later revised by a constitutional committee. Among its provisions were a Western-style bill of rights, creation of a National Council of Democracy to oversee the guarantee of those rights, a governmental advisory board on economic and social issues, and an independent judiciary. After approval by the National Assembly, PDG Central Committee, and the President, the Assembly unanimously adopted the constitution in March 1991. Multiparty legislative elections were held in 1990–1991 when opposition parties had not been declared formally legal. In January 1991, the Assembly passed by unanimous vote a law governing the legalization of opposition parties.[17]

After President Omar Bongo was re-elected in 1993, in a disputed election where only 51% of votes were cast, social and political disturbances led to the 1994 Paris Conference and Accords. These provided a framework for the next elections. Local and legislative elections were delayed until 1996–1997. In 1997, constitutional amendments put forward years earlier were adopted to create the Senate and the position of Vice President, and to extend the President's term to seven years.[17]

In October 2009, President Ali Bongo Ondimba began efforts to streamline the government. In an effort to reduce corruption and government bloat, he eliminated 17 minister-level positions, abolished the Vice Presidency and reorganized the portfolios of some ministries, bureaus and directorates. In November 2009, President Bongo Ondimba announced a new vision for the modernization of Gabon, called "Gabon Emergent". This program contains three pillars: Green Gabon, Service Gabon, and Industrial Gabon. The goals of Gabon Emergent are to diversify the economy so that Gabon becomes less reliant on petroleum, to eliminate corruption, and to modernize the workforce. Under this program, exports of raw timber have been banned, a government-wide census was held, the work day was changed to eliminate a long midday break, and a national oil company was created.[17]

On 25 January 2011, opposition leader André Mba Obame claimed the presidency, saying the country should be run by someone the people really wanted. He selected 19 ministers for his government, and the entire group, along with hundreds of others, spent the night at the United Nations headquarters. On January 26, the government dissolved Mba Obame's party. AU chairman Jean Ping said that Mba Obame's action "hurts the integrity of legitimate institutions and also endangers the peace, the security and the stability of Gabon."[25] Interior Minister Jean-François Ndongou accused Mba Obame and his supporters of treason.[25] The UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-moon, said that he recognized Ondimba as the only official Gabonese president.[26][self-published source?]

The 2016 presidential election was disputed, with "very close" official results reported. Protests broke out in the capital and met a repression which culminated in the alleged bombing of opposition party headquarters by the presidential guard. Between 50 and 100 citizens were killed by security forces and 1,000 arrested.[27] International observers criticized irregularities, including unnaturally high turnout reported for some districts. The country's supreme court threw out some suspect precincts, and the ballots have been destroyed. The election was declared in favour of the incumbent Ondimba. The European Parliament issued two resolutions denouncing the unclear results of the election and calling for an investigation on the human rights violations.[28]

A few days after the controversial presidential election in August 2023, a group of military officials declared a military coup and that they had overthrown the government and deposed Ali Bongo Ondimba. The announcement came hours after Ali Bongo was officially re-elected for a third term.[29] General Brice Oligui Nguema was appointed as the transitional leader. This event marked the eighth instance of military intervention in the region since 2020, raising concerns about democratic stability.[30]

Foreign relations

[edit]

Since independence, Gabon has followed a nonaligned policy, advocating dialogue in international affairs and recognizing each side of divided countries. In intra-African affairs, it espouses development by evolution rather than revolution and favours regulated private enterprise as the system most likely to promote rapid economic growth. It involved itself in mediation efforts in Chad, the Central African Republic, Angola, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (D.R.C.), and Burundi. In December 1999, through the mediation efforts of President Bongo, a peace accord was signed in the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville) between the government and most leaders of an armed rebellion. President Bongo was involved in the continuing D.R.C. peace process, and played a role in mediating the crisis in Ivory Coast.

Gabon is a member of the United Nations (UN) and some of its specialized and related agencies, and of the World Bank; the IMF; the African Union (AU); the Central African Customs Union/Central African Economic and Monetary Community (UDEAC/CEMAC); EU/ACP association under the Lomé Convention; the Communaute Financiere Africaine (CFA); the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC); the Nonaligned Movement; and the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS/CEEAC). In 1995, Gabon withdrew from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), rejoining in 2016. Gabon was elected to a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council for January 2010 through December 2011 and held the rotating presidency in March 2010.[17] In 2022, Gabon joined the Commonwealth of Nations.[31] In 2024, ruling junta leader Brice Oligui Nguema assured American and French leaders that Gabon would be an ally of the West moving forward, as a part of his broader plan to solve the ongoing debt crisis.[32]

Military

[edit]It has a professional military of about 5,000 personnel, divided into army, navy, air force, gendarmerie, and police force. A 1,800-member guard provides security for the president.[17]

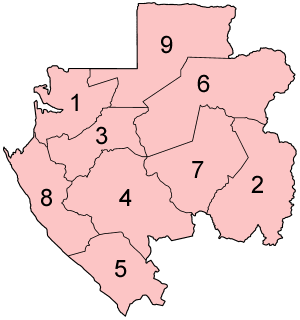

Administrative divisions

[edit]

It is divided into 9 provinces which are subdivided into 50 departments. The president appoints the provincial governors, the prefects, and the subprefects.[17]

The provinces are (capitals in parentheses):

- Estuaire (Libreville)

- Haut-Ogooué (Franceville)

- Moyen-Ogooué (Lambaréné)

- Ngounié (Mouila)

- Nyanga (Tchibanga)

- Ogooué-Ivindo (Makokou)

- Ogooué-Lolo (Koulamoutou)

- Ogooué-Maritime (Port-Gentil)

- Woleu-Ntem (Oyem)

Geography

[edit]

Gabon is located on the Atlantic coast of central Africa on the equator, between latitudes 3°N and 4°S, and longitudes 8° and 15°E. Gabon has an equatorial climate with a system of rainforests, with 89.3% of its land area forested.[33]

There are coastal plains (ranging between 20 and 300 km [10 and 190 mi] from the ocean's shore), the mountains (the Cristal Mountains to the northeast of Libreville, the Chaillu Massif in the centre), and the savanna in the east. The coastal plains form a section of the World Wildlife Fund's Atlantic Equatorial coastal forests ecoregion and contain patches of Central African mangroves including on the Muni River estuary on the border with Equatorial Guinea.[34]

Geologically, Gabon is primarily Archaean and Palaeoproterozoic igneous and metamorphic basement rock, belonging to the stable continental crust of the Congo Craton. Some formations are more than 2 billion years old. Some rock units are overlain by marine carbonate, lacustrine and continental sedimentary rocks, and unconsolidated sediments and soils that formed in the last 2.5 million years of the Quaternary. The rifting apart of the supercontinent Pangaea created rift basins that filled with sediments and formed the hydrocarbons.[35] There are Oklo reactor zones, a natural nuclear fission reactor on Earth which was active 2 billion years ago. The site was discovered during uranium mining in the 1970s to supply the French nuclear power industry.

Its largest river is the Ogooué which is 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) long. It has 3 karst areas where there are hundreds of caves located in the dolomite and limestone rocks. A National Geographic Expedition visited some caves in the summer of 2008 to document them.[36]

In 2002, President Omar Bongo Ondimba designated roughly 10% of the nation's territory to be part of its national park system (with 13 parks in total). The National Agency for National Parks manages Gabon's national park system. Gabon had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 9.07/10, ranking it 9th globally out of 172 countries.[37]

Wildlife

[edit]Gabon has a large number of protected animal and plant species. The country's biodiversity is one of the most varied on the planet.[38]

Fauna of Gabon

[edit]Gabon is home of 604 species of birds, 98 species of amphibians, between 95 and 160 species of reptiles and 198 different species of mammals.[39] In Gabon there are rare species, such as the Gabon pangolin and the grey-necked rockfowl, or endemics, such as the Gabon guenon.

The country is one of the most varied and important fauna reserves in Africa:[40] it is an important refuge for chimpanzees (whose number, in 2003, was estimated between 27,000 and 64,000)[citation needed] and gorillas (28,000-42,000 estimated in 1983).[41] The "Gorilla and Chimpanzee Study Station" inside the Lopé National Park[citation needed] is dedicated to their study.

It is also home to more than half the population of African forest elephants,[42] mostly in Minkébé National Park.[citation needed] Gabon's national symbol is the black panther.[43]

Flora of Gabon

[edit]More than 10,000 species of plants, and 400 species of trees form the flora of Gabon. Gabon's rainforest is considered the densest and most virgin in Africa. However, the country's enormous population growth is causing heavy deforestation that threatens this valuable ecosystem. Likewise, poaching endangers wildlife. Gabon's national flower is Delonix Regia.

Economy

[edit]

Oil revenues constitute roughly 46% of the government's budget, 43% of the gross domestic product (GDP), and 81% of exports. Oil production declined from its higher point of 370,000 barrels per day in 1997. Some estimates suggest that Gabonese oil will be expended by 2025. Planning is beginning for an after-oil scenario.[17] The rich Grondin Oil Field was discovered in 1971 in 50 m (160 ft) water depths 40 km (25 mi) offshore in an anticline salt structural trap in Batanga sandstones of Maastrichtian age, but about 60% of its estimated reserves had been extracted by 1978.[44]

As of 2023, Gabon produced about 200,000 barrels a day (bpd) of crude oil.[45]

"Overspending" on the Trans-Gabon Railway, the CFA franc devaluation of 1994, and periods of lower oil prices caused debt problems.[17]

Successive International Monetary Fund (IMF) missions have criticized the Gabonaise government for overspending on off-budget items (in good years and bad), over-borrowing from the central bank, and slipping on the schedule for privatization and administrative reform. In September 2005 Gabon successfully concluded a 15-month Stand-By Arrangement with the IMF. A three-year Stand-By Arrangement with IMF was approved in May 2007. Because of the financial crisis and social developments surrounding the death of President Omar Bongo and the elections, Gabon was unable to meet its economic goals under the Stand-By Arrangement in 2009.[17]

Gabon's oil revenues have given it a per capita GDP of $8,600. A "skewed income distribution" and "poor social indicators" are "evident".[46] The richest 20% of the population earn over 90% of the income while about a third of the Gabonese population lives in poverty.[17]

The economy is dependent on extraction. Before the discovery of oil, logging was the "pillar" of the Gabonese economy. Then, logging and manganese mining are the "next-most-important" income generators. Some explorations suggest the presence of the world's largest unexploited iron ore deposit. For some who live in rural areas without access to employment opportunity in extractive industries, remittances from family members in urban areas or subsistence activities provide income.[17]

Foreign and local observers have lamented the lack of diversity in the Gabonese economy. Factors that have "limited the development of new industries" were listed as follows:

- the market is "small", about a million

- dependent on imports from France

- unable to capitalize on regional markets

- entrepreneurial zeal not always present among the Gabonese

- a "fairly regular" stream of oil "rent", even if it is diminishing

Further investment in the agricultural or tourism sectors is "complicated by poor infrastructure". Some processing and service sectors are "largely dominated by a few prominent local investors".[17]

At World Bank and IMF insistence, the government embarked in the 1990s on a program of privatization of its state-owned companies and administrative reform, including reducing public sector employment and salary growth. The government has voiced a commitment to work toward an economic transformation of the country.[17]

Energy

[edit]Transport

[edit]Demographics

[edit]| Year | Million |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 0.5 |

| 2000 | 1.2 |

| 2021 | 2.3 |

It has a population of approximately 2.3 million.[47][48] Historical and environmental factors caused its population to decline between 1900 and 1940.[49] It has one of the lowest population densities of any country in Africa,[17] and the fourth highest Human Development Index in Sub-Saharan Africa.[11]

Ethnic groups

[edit]Gabon has at least 40 ethnic groups,[17] including Fang, Myènè, Punu-Échira, Nzebi-Adouma, Teke-Mbete, Mèmbè, Kota, Akélé.[50] There are indigenous Pygmy peoples: the Bongo, and Baka.[17] The latter speak the only non-Bantu language in Gabon. More than 10,000 native French live in Gabon, including an estimated 2,000 dual nationals.[17]

Some ethnicities are spread throughout Gabon, leading to contact, interaction among the groups, and intermarriage.

Population centres

[edit]

| Rank | City | Population | Province | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 census[51] | 2013 census[51] | |||

| 1. | Libreville | 538,195 | 703,940 | Estuaire |

| 2. | Port-Gentil | 105,712 | 136,462 | Ogooué-Maritime |

| 3. | Franceville | 103,840 | 110,568 | Haut-Ogooué |

| 4. | Owendo | 51,661 | 79,300 | Estuaire |

| 5. | Oyem | 35,241 | 60,685 | Woleu-Ntem |

| 6. | Moanda | 42,703 | 59,154 | Haut-Ogooué |

| 7. | Ntoum | 12,711 | 51,954 | Estuaire |

| 8. | Lambaréné | 24,883 | 38,775 | Moyen-Ogooué |

| 9. | Mouila | 21,074 | 36,061 | Ngounié |

| 10. | Akanda | – | 34,548 | Estuaire |

Languages

[edit]French is the sole official language. It is estimated that 80% of the population can speak French, and that 30% of Libreville residents are native speakers of the language.

Nationally, a majority of the Gabonese people speak indigenous languages, according to their ethnic group, while this proportion is lower than in most other Sub-Saharan African countries. The 2013 census found that 63.7% of Gabon's population could speak a Gabonese language, broken down by 86.3% in rural areas and 60.5% in urban areas speaking at least one national language.[52]

Religion

[edit]Religion in Gabon by the Association of Religion Data Archives (2015)[53]

Religions practised in Gabon include Christianity (Roman Catholicism and Protestantism), Islam, and traditional indigenous religious beliefs.[54] Some people practise elements of both Christianity and indigenous religious beliefs.[54] Approximately 79% of the population (53% Catholic) practise one of the denominations of Christianity; 10% practise Islam (mainly Sunni); the remainder practise other religions.

Health

[edit]A private hospital was established in 1913 in Lambaréné by Albert Schweitzer. By 1985 there were 28 hospitals, 87 medical centres, and 312 infirmaries and dispensaries. As of 2004[update], there were an estimated 29 physicians per 100,000 people, and "approximately 90% of the population had access to health care services".

In 2000, 70% of the population had access to "safe drinking water" and 21% had "adequate sanitation". A government health program treats such diseases as leprosy, sleeping sickness, malaria, filariasis, intestinal worms, and tuberculosis. Rates for immunization of children under the age of 1 were 97% for tuberculosis and 65% for polio. Immunization rates for DPT and measles were 37% and 56% respectively. Gabon has a domestic supply of pharmaceuticals from a factory in Libreville.

The total fertility rate has decreased from 5.8 in 1960 to 4.2 children per mother during childbearing years in 2000. 10% of all births were "low birth weight". The maternal mortality rate was 520 per 100,000 live births as of 1998. In 2005, the infant mortality rate was 55.35 per 1,000 live births and life expectancy was 55.02 years. As of 2002, the overall mortality rate was estimated at 17.6 per 1,000 inhabitants.

The HIV/AIDS prevalence is estimated to be 5.2% of the adult population (ages 15–49).[55] As of 2009[update], approximately 46,000 people were living with HIV/AIDS.[56] There were an estimated 2,400 deaths from AIDS in 2009 – down from 3,000 deaths in 2003.[57]

Education

[edit]Its education system is regulated by two ministries: the Ministry of Education, in charge of pre-kindergarten through the last high school grade, and the Ministry of Higher Education and Innovative Technologies, in charge of universities, higher education, and professional schools.

Education is compulsory for children ages 6 to 16 under the Education Act. Some children in Gabon start their school lives by attending nurseries or "Crèche", then kindergarten known as "Jardins d'Enfants". At age 6, they are enrolled in primary school, "École Primaire" which is made up of 6 grades. The next level is "École Secondaire", which is made up of 7 grades. The planned graduation age is 19 years old. Those who graduate can apply for admission at institutions of higher learning, including engineering schools or business schools. As of 2012, the literacy rate of a population ages 15 and above was 82%.[58]

The government has used oil revenue for school construction, paying teachers' salaries, and promoting education, including in rural areas. Maintenance of school structures, and teachers' salaries, has been declining. In 2002 the gross primary enrollment rate was 132%, and in 2000 the net primary enrollment rate was 78%. Gross and net enrollment ratios are based on the number of students formally registered in primary school. As of 2001, 69% of children who started primary school were "likely" to reach grade 5. Problems in the education system include "poor management and planning, lack of oversight, poorly qualified teachers", and "overcrowded classrooms".[59] There are various universities in Gabon which are being chartered, licensed or accredited by the appropriate Gabonese higher education-related organization.[60]

Culture

[edit]

Gabon's cultural heritage, rooted in an oral tradition for much of its history, began to flourish with the spread of literacy in the 21st century. Rich in folklore and mythology, the country is home to a tapestry of traditions that have been preserved and passed down through generations. Custodians of these traditions, known as "raconteurs," diligently work to ensure their continuity, nurturing practices like the mvett among the Fangs and the Ingwala among the Nzebis.

Central to Gabonese culture are its iconic masks, each imbued with unique significance and craftsmanship. Among these are the renowned n'goltang masks of the Fang people and the intricate reliquary figures of the Kota. These masks hold crucial roles in various ceremonies, including those marking significant life events such as marriage, birth, and funerals. Crafted by traditionalists using rare local woods and other precious materials, these masks serve as artistic expressions and vessels of cultural heritage.

Music

[edit]It has an array of folk styles. Imported rock and hip hop from the US and UK are in Gabon, as are rumba, makossa and soukous. Some folk instruments include the obala, the ngombi, the balafon and drums.[61]

Media

[edit]Radio-Diffusion Télévision Gabonaise (RTG) which is owned and operated by the government broadcasts in French and indigenous languages. Colour television broadcasts have been introduced in some cities. In 1981, a commercial radio station, Africa No. 1, began operations. It has participation from the French and Gabonese governments and private European media.

In 2004, the government operated 2 radio stations and another 7 were privately owned. There were 2 government television stations and 4 privately owned. In 2003, there were an estimated 488 radios and 308 television sets for every 1,000 people. About 11.5 of every 1,000 people were cable subscribers. In 2003, there were 22.4 personal computers for every 1,000 people and 26 of every 1,000 people had access to the Internet. The national press service is the Gabonese Press Agency which publishes a daily paper, Gabon-Matin (circulation 18,000 as of 2002).

L'Union in Libreville, the government-controlled daily newspaper, had an average daily circulation of 40,000 in 2002. The weekly Gabon d'Aujourdhui is published by the Ministry of Communications. There are about 9 privately owned periodicals which are either independent or affiliated with political parties. These publish in certain numbers that have been delayed by financial constraints. The constitution of Gabon provides for free speech and a free press, and the government supports these rights. Some periodicals actively criticize the government and foreign publications are available.

Cuisine

[edit]Gabonese cuisine is influenced by French cuisine, and staple foods are available.[62]

Sports

[edit]The Gabon national football team has represented the nation since 1962.[63] The Under-23 football team won the 2011 CAF U-23 Championship and qualified for the 2012 London Olympics. Gabon were joint hosts, along with Equatorial Guinea, of the 2012 Africa Cup of Nations,[64] and the sole hosts of the competition's 2017 tournament.[65]

The Gabon national basketball team, nicknamed Les Panthères,[66] finished 8th at the AfroBasket 2015.

Gabon has competed at most Summer Olympics since 1972. Anthony Obame won a silver medal in taekwondo at the 2012 Olympics held in London.[67]

Gabon has recreational fishing and is considered the "best place in the world" to catch Atlantic tarpon.[68]

Since 2006, Gabon has hosted La Tropicale Amissa Bongo, a professional week long bicycle race which includes both European and African teams.[69]

Chris Silva is a Gabonese basketball player in the Israeli Basketball Premier League.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Country Summary".

- ^ Obangome, Gerauds Wilfried (30 August 2023). "Gabonese military officers announce on television they have seized power". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "General Nguema appointed transitional president of Gabon following coup". Anadolu Agency. Kigali, Rwanda. 30 August 2023. Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "Gabon: Joseph Owondault Berre nommé vice-président de la transition". ACP (in French). 12 September 2023.

- ^ "Gabon junta names former PM Raymond Ndong Sima as interim PM - statement". Reuters. 7 September 2023. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ "Gabon". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Gabon)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Gabun und Niger: "Wichtig, die Länder individuell zu betrachten"". tagesschau.de (in German). Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ "Gabon - OPEC Fund for International Development". Archived from the original on 22 April 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ *Gates, Henry Louis & Kwame Anthony Appiah (1999). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. New York City: Basic Civitas Books. pp. 1468. ISBN 0-465-00071-1.

- ^ Goldie, George Dashwood Taubman (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). pp. 464–465.

- ^ "Gabon country profile". BBC News. 24 September 2018. Archived from the original on 25 September 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "Gabon". Archontology. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Background note: Gabon, U.S. Department of State (4 August 2010).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Background note: Gabon, U.S. Department of State (4 August 2010).

- ^ "Soldiers in Gabon try to seize power in failed coup attempt". Bnonews.com. 7 January 2019. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Gabon and Togo join the Commonwealth" (Press release). Commonwealth of Nations. 25 June 2022. Archived from the original on 21 July 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ "Gabon military officers claim power, say election lacked credibility". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Gabonese military officers announce they have seized power of oil-rich country". Reuters. 30 August 2023. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Gabon coup leaders name Gen Brice Oligui Nguema as new leader". BBC News. 31 August 2023. Archived from the original on 31 August 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ^ "Gabon coup leader Brice Nguema vows free elections - but no date". BBC News. 4 September 2023. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ "Journal de l'Afrique - Nouvelle constitution au Gabon, le référendum fixé au 16 novembre". France 24 (in French). 18 October 2024. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ a b Goma, Yves Laurent (26 January 2011). "Gabon opposition leader declares himself president". Winston-Salem Journal. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ^ WWW.IBPUS.COM (13 March 2019). Gabon: Doing Business, Investing in Gabon Guide Volume 1 Strategic, Practical Information, Regulations, Contacts. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781514526613. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2020.[self-published source]

- ^ "'Between 50 and 100 killed' in Gabon election violence, presidential challenger tells FRANCE 24 – France 24". France 24. 6 September 2016. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Motion for a resolution on Gabon, repression of the opposition – B8-0526/2017". Europarl.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ Walsh, Declan (30 August 2023). "Gabon Military Officers Say They Are Seizing Power". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 3 September 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Wilfried Obangome, Gerauds (30 August 2023). "Gabon army officers say they have seized power after election in oil-rich country". Reuters. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "West African nations Gabon and Togo join Commonwealth". France 24. 25 June 2022. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Gabon: Will the coup lead to democracy?". Global Bar Magazine (in Swedish). 7 June 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- ^ "Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015 website". FAO. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Schluter, Thomas (2006). Geological Atlas of Africa. Springer. pp. 110–112.

- ^ "Expedition website". Archived from the original on 20 April 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2008.

- ^ Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- ^ Wilks, Chris (1990). La conservation des ecosystèmes forestiers du Gabon (in French). UICN. p. 16. ISBN 2-88032-988-4. Archived from the original on 7 September 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ "Le Gabon, berceau de la biodiversité" (in French). Archived from the original on 3 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Ministère des Eaux et Forêts (May 2011). "Guide juridique pour la protection de la faune sauvage en République du Gabon" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Tutin, C. E. G.; Fernandez, M. (1984). "Nationwide census of gorilla (gorilla g. gorilla) and chimpanzee (Pan t. troglodytes) populations in Gabon". American Journal of Primatology. 6 (4): 313–336. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350060403. PMID 32160718. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Mutsaka, Farai (18 November 2021). "Gabon is last bastion of endangered African forest elephants". AP News. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Gabon reveal 2017 Nations Cup mascot". BBC Sport. 25 March 2016. Archived from the original on 15 March 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Vidal, J., "Geology of Grondin Field, 1980", in Giant Oil and Gas Fields of the Decade: 1968–1978, AAPG Memoir 30, Halbouty, M.T., editor, Tulsa: American Association of Petroleum Geologists, ISBN 0891813063, pp.577–590.

- ^ Bousso, Ron (30 August 2023). "Gabon's Assala Energy says oil production unaffected by coup". Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Gabon". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ^ "Gabon – The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Gabon: Provinces, Cities & Urban Places – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". Citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ^ "Résultats Globaux du Recensement Général de la Population et des Logements de 2013 du Gabon (RGPL-2013)" (PDF). Direction Générale des Statistiques du Gabon. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Gabon". Association of Religion Data Archives. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Gabon. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Gabon. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007)

- ^ "COUNTRY COMPARISON :: HIV/AIDS – ADULT PREVALENCE RATE". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "COUNTRY COMPARISON :: HIV/AIDS – PEOPLE LIVING WITH HIV/AIDS". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "Country comparison :: HIV/AIDS – deaths". CIA World Factbook. Archived from the original on 21 May 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ "Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Gabon". 2005 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor . Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2006).

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Gabon". 2005 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor . Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2006).

- ^ "Top Universities in Gabon | 2024 University Rankings". www.4icu.org. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ "national-instrument". symbolhunt.com. 28 December 2020. Archived from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Foster, Dean (2002). The Global Etiquette Guide to Africa and the Middle East: Everything You Need to Know for Business and Travel Success Archived 11 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. John Wiley & Sons. p. 177. ISBN 0471272825

- ^ "Gabon: Gabon Fédération Gabonaise de Football". Fifa.com. FIFA. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "Gabon will host the 2012 Africa Cup of Nations final". BBC Sport. BBC. 29 January 2010. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "Gabon named hosts of AFCON 201". Cafonline.com. CAF. 8 April 2015. Archived from the original on 9 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ Afrobasket 2015 : Les Panthères en mise au vert en Serbie Archived 18 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine, GABON Review, 19 August 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2016. (in French)

- ^ "History-making Obame rues inexperience". Archived from the original on 15 August 2012.

- ^ Olander, Doug (29 May 2014). "World's Best Tarpon Fishing Spots". sportfishingmag.com. Sport Fishing Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ "La Tropicale Amissa Bongo". Pro Cycling Stats. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-report-on-international-religious-freedom/gabon/

Bibliography

[edit]- Bachmann, Olaf. "Gabon: An Uneasy Civil‒Military Concord." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics (2020).

- Gardinier, David E. "France and Gabon since 1993: The reshaping of a neo-colonial relationship." Journal of Contemporary African Studies 18.2 (2000): 225–242. online

- Ghazvinian, John (2008). Untapped: The Scramble for Africa's Oil. Orlando: Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-101138-4.

- Gray, Christopher J. "Cultivating citizenship through xenophobia in Gabon, 1960-1995." Africa today 45.3/4 (1998): 389-409 online

- Gray, Christopher. "Who Does Historical Research in Gabon? Obstacles to the Development of a Scholarly Tradition1." History in Africa 21 (1994): 413–433.

- Jean-Baptiste, Rachel. Multiracial Identities in Colonial French Africa: Race, Childhood, and Citizenship (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

- Ngolet, François. "Ideological manipulations and political longevity: the power of Omar Bongo in Gabon since 1967." African Studies Review 43.2 (2000): 55–71. online

- Rich, Jeremy (2007). A Workman Is Worthy of His Meat: Food and Colonialism in the Gabon Estuary. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-0741-7.

- Shaxson, Nicholas (2007). Poisoned Wells: The Dirty Politics of African Oil. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7194-4.

- Warne, Sophie (2003). Bradt Travel Guide: Gabon and São Tomé and Príncipe. Guilford, CT: Chalfont St. Peter. ISBN 1-84162-073-4.

- Yates, Douglas A. (1996). The Rentier State in Africa: Oil Rent Dependency and Neo-colonialism in the Republic of Gabon. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press. ISBN 0-86543-520-0.

- Yates, Douglas A. Historical dictionary of Gabon (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017) online Archived 7 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Yates, Douglas. "The dynastic republic of Gabon." Cahiers d’études africaines (2019): 483–513. online Archived 4 July 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- Yates, Douglas A. "The History of Gabon." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History (2020).

- Yates, Douglas Andrew. The rentier state in Africa: Oil rent dependency and neocolonialism in the Republic of Gabon (Africa World Press, 1996) online Archived 7 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

External links

[edit]- Gabon

- Central African countries

- Former French colonies

- French-speaking countries and territories

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Member states of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie

- Member states of the African Union

- Member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

- Member states of OPEC

- Member states of the United Nations

- Military dictatorships

- Republics

- Republics in the Commonwealth of Nations

- States and territories established in 1960

- 1960 establishments in Africa

- Countries in Africa