Ary Scheffer

Ary Scheffer | |

|---|---|

Self Portrait at the age of 43, c. 1838 | |

| Born | 10 February 1795 Dordrecht, Netherlands |

| Died | 15 June 1858 (aged 63) Argenteuil, France |

| Nationality | Dutch, French |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Romanticism |

Ary Scheffer (10 February 1795 – 15 June 1858) was a Dutch-French Romantic painter.[1] He was known mostly for his works based on literature, with paintings based on the works of Dante, Goethe, Lord Byron and Walter Scott,[2] as well as religious subjects. He was also a prolific painter of portraits of famous and influential people in his lifetime. Politically, Scheffer had strong ties to King Louis Philippe I, having been employed as a teacher of the latter's children, which allowed him to live a life of luxury for many years until the French Revolution of 1848.

Life

[edit]

Scheffer was the son of Johan Bernard Scheffer (1765–1809), a portrait painter who was born in Homberg upon Ohm or Cassel (both presently in Germany; the latter has been spelled as Kassel since 1926) and moved to the Netherlands in his youth, and Cornelia Lamme (1769–1839), a portrait miniature painter and daughter of landscape painter Arie Lamme of Dordrecht, for whom Arij (later "Ary") was named. Ary Scheffer had two brothers, the journalist and writer Karel Arnold Scheffer (1796–1853) and the painter Hendrik Scheffer (1798–1862). His parents educated him and he attended the drawing academy in Amsterdam from the age of 11 years. In 1808 his father became the court painter of Louis Bonaparte in Amsterdam, yet his father died one year later. Encouraged by Willem Bilderdijk, Ary moved to Lille, France, for further study after the death of his father. In 1811 he and his mother, who greatly influenced his career, moved to Paris, France, where he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts as a pupil of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin. His brothers followed them to Paris later.[3]

Scheffer started exhibiting at the Salon de Paris in 1812. He began to be recognized in 1817, and in 1819 he was asked to make a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette. Perhaps because of Lafayette's acquaintances, Scheffer and his brothers were politically active throughout their lives and he became a prominent Philhellene.[3]

In 1822 he became drawing teacher to the children of Louis Philippe I, the Duke of Orléans. Because of his connection with them, he obtained many commissions for portraiture and other work. In 1830 riots against the rule of King Charles X resulted in his overthrow. On 30 July, Scheffer and influential journalist Adolphe Thiers rode from Paris to Orléans to ask Louis Philippe I to lead the resistance, and a few days later he became "King of the French".[3]

That same year, Scheffer's daughter Cornélia was born. He registered the name of her mother as "Maria Johanna de Nes", but nothing is known of her and she may have died soon after Cornelia's birth. Considering that his grandmother's name was "Johanna de Nes", it has been speculated that he kept the name of Cornelia's mother secret so as not to compromise the reputation of a noble family. Cornelia Scheffer (1830–1899) became a sculptor and painter in her own right.[4] Scheffer's mother did not know of her namesake granddaughter until 1837, after which she cared for her until she died only two years later.[3] Scheffer became an associate member of the Royal Institute of the Netherlands in 1846, and resigned in 1851.[5]

Scheffer and his family prospered during the reign of Louis Philippe I, who abdicated on 24 February 1848. Scheffer and Hendrik were inundated with artistic commissions, and they taught numerous students in their workshop in Paris, so many that of the works produced during this period that bear his signature the number that he actually made himself cannot be verified.[3]

Scheffer was elevated as commander of the Legion of Honour in 1848. As a captain of the Garde Nationale he escorted the French royal family in its escape from the Tuileries and escorted the Duchess d'Orléans to the Chambre des Députés, where she in vain proposed her son as the next monarch of France. Scheffer fought in the army of Cavaignac during the June Days Uprising in Paris of 23 to 26 June 1848. The cruelty and hatred that the governmental faction exhibited and the misery of the lower classes so shocked him that he withdrew from politics and refused to make portraits of the family of Napoléon III, who reigned after the Uprising. On 16 March 1850 he married Sophie Marin, the widow of General Baudrand, and on 6 November of that year he finally became a French citizen. He continued to frequently travel to the Netherlands, and traveled to Belgium, Germany, and England, but a heart condition impaired his activity and eventually caused his death in 1858 in his summer house in Argenteuil.[3] He is buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre.

Works

[edit]When Scheffer left Guérin's studio, Romanticism had come into vogue in France, with such painters as Xavier Sigalon, Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault. Scheffer did not show much affinity with their work and developed his own style, which has been called "frigidly classical".[6]

Scheffer often painted subjects from literature, especially the works of Dante, Byron and Goethe. Two versions of Dante and Beatrice have been preserved at Wolverhampton Art Gallery, United Kingdom,[7] and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, US.[8] His L'Enterrement du Jeune Pêcheur, illustrating a scene from Walter Scott's The Antiquary and taking inspiration from David Wilkie's Distraining for Rent, was exhibited at the Salon of 1824.[2] Particularly highly praised was his Francesca da Rimini, painted in 1836, which illustrates a scene from Dante Alighieri's Inferno. In the piece the entwined bodies of Francesca di Rimini and Paolo Malatesta swirl around in the never-ending tempest that is the second circle of Hell. The illusion of movement is created by the drapery that envelopes the couple, as well as by Francesca's flowing hair. These two figures create a diagonal line that intersects the majority of the canvas creating not only a sense of movement, but also giving the painting an air of instability.[original research?] Francesca clings to Paolo as he turns his face away in anguish. There are an additional two figures in the image: hidden in the background, the poets Dante and Virgil look on as they make their way through the nine circles of Hell.

Scheffer's popular Faust-themed paintings include Margaret at her wheel; Faust doubting; Margaret at the Sabbat; Margaret leaving church; The garden walk, and Margaret at the well. In 1836, he painted two pictures of Goethe's character Mignon: Mignon desires her fatherland (1836), and Mignon yearns for heaven (1851).[9]

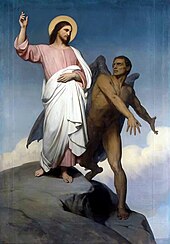

He now turned to religious subjects: Christus Consolator (1836) was followed by Christus Remunerator, The shepherds led by the star (1837), The Magi laying down their crowns, Christ in the Garden of Olives, Christ bearing his Cross, Christ interred (1845), and St Augustine and Monica (1846).

One of the reduced versions of his Christus Consolator (the prime version today to be found in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam), lost for 70 years, was rediscovered in a janitor's closet in Gethsemane Lutheran Church in Dassel, Minnesota, in 2007. It has been restored and is on display at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.[10]

Scheffer was also an accomplished portrait painter, finishing 500 portraits in total. His subjects included composers Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt, the Marquis de la Fayette, Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Alphonse de Lamartine, Charles Dickens, Duchess de Broglie,[11] Talleyrand[11] and Queen Marie Amélie.

After 1846, he ceased to exhibit. His strong ties with the royal family caused him to fall out of favour when, in 1848, the Second Republic came into being. Scheffer was made commander of the Legion of Honour in 1848, that is, after he had wholly withdrawn from the Salon. Shut up in his studio, he produced many paintings that were only exhibited after his death in 1858.[12]

The works first exhibited posthumously include Sorrows of the earth, and the Angel announcing the Resurrection, which he had left unfinished. By the time of his death, his reputation was damaged and was further undermined by the sale of the Paturle Gallery, which contained many of his most celebrated achievements: though his paintings were praised for their charm and facility, they were condemned for poor use of color and vapid sentiment.[12]

Friends and family

[edit]

At various times Maurice Sand, Scheffer, Charles Gounod, Hector Berlioz were in relationships with Pauline Viardot—in letters they claimed that they were in love with her.[13] She wrote in one letter:

Louis and Scheffer (Scheffer was the best friend of Louis Viardot, husband of Pauline Viardot) has always been my dearest of friends, and it is sad, that I was never able to respond to the hot and deep love of Louis, despite all my volition.[14]

She was married to Louis Viardot at 18 years old, when her husband was a director of an Italian opera house in Paris and a friend of Scheffer. Scheffer was a confidant of Pauline Viardot and a friend of her family until his death.[14][15]

In 1850 Scheffer became a French citizen and married Sophie Marin, the widow of General Marie Étienne François Henri Baudrand. Marin died in 1856.[16]

His younger brother Hendrik Scheffer, born in The Hague on 27 September 1798, was also a painter.[17]

Gallery

[edit]-

The Death of Malvina, 1811

-

The Death of Géricault, 1824

-

A convalescent mother and her children, 1824

-

Portrait of Franz Liszt, 1837

-

Faust and Marguerite in the Garden, 1846

-

Le petit atelier, 1850

-

Marguerite at the fountain, 1858

-

Ary Scheffer - Franz Liszt

-

Lamartine par Ary Scheffer

-

Self-portrait

-

Chopin by Scheffer

-

Charlotte, wife of Anselm Salomon von Rothschild

-

Saint Louis visitant les pestiférés (1822)

-

Death of Saint Louis

See also

[edit]- Musée de la Vie Romantique, Hôtel Scheffer-Renan, Paris

References

[edit]- ^ Wood, James, ed. (1907). . The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

- ^ a b Macmillan, Duncan (2023), Scotland and the Origins of Modern Art, Lund Humphries, London, pp. 167 - 182, ISBN 978-1-84822-633-3

- ^ a b c d e f Scheffer, Arij (1795–1858) in the Biographical Dictionary of the Netherlands: 1880–2000 (in Dutch)

- ^ Scheffer, Cornelia (1830–1899) in the Biographical Dictionary of the Netherlands: 1880–2000 (in Dutch)

- ^ "A. Scheffer (1795–1858)". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Murray, P. & L. (1996), Dictionary of art and artists. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-051300-0.

- ^ Smyth, Patricia. "The Vision: Dante and Beatrice". The National Inventory of Continental European Paintings. VADS. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Dante and Beatrice". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 11 November 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Ary Scheffer – Societyschilder in Parijs". Dordrechts Museum.

- ^ Wagener, Anne-Marie; Pleshek, Tammy (31 March 2009). "Scheffer's Painting of Christ the Comforter Discovered in a Church in Rural Minnesota" (Press release). Minneapolis, Minnesota: Minneapolis Institute of Art. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ^ a b Reynolds, Francis J., ed. (1921). . Collier's New Encyclopedia. New York: P. F. Collier & Son Company.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Scheffer, Ary". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 316.

- ^ Журнальный зал >> Author:Ирина ЧАЙКОВСКАЯ "Полина Виардо: возможность дискуссии". Chapter: "Безобразная красавица".

- ^ a b Журнальный зал >> Author:Ирина ЧАЙКОВСКАЯ "Полина Виардо: возможность дискуссии". Chapter: "Монашка или женщина-вамп?"

- ^ Barbara Kendall-Davis. P. 397.

- ^ "Ary Scheffer Paintings, Scheffer Reproductions, Biography". Archived from the original on 28 August 2008.

- ^

Bryan, Michael (1889). "Scheffer, Hendrik". In Armstrong, Sir Walter; Graves, Robert Edmund (eds.). Bryan's Dictionary of Painters and Engravers (L–Z). Vol. II (3rd ed.). London: George Bell & Sons.

Bryan, Michael (1889). "Scheffer, Hendrik". In Armstrong, Sir Walter; Graves, Robert Edmund (eds.). Bryan's Dictionary of Painters and Engravers (L–Z). Vol. II (3rd ed.). London: George Bell & Sons.

Further reading

[edit]- Morris, Edward (1985). "Ary Scheffer and his English Circle". Oud Holland. 99 (4): 294–323. doi:10.1163/187501785X00143. JSTOR 42711190.

External links

[edit] Media related to Ary Scheffer at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ary Scheffer at Wikimedia Commons- Ary Scheffer at Art Renewal Center

- 1795 births

- 1858 deaths

- 19th-century Dutch painters

- Immigrants to the Netherlands

- Immigrants to France

- Dutch male painters

- 19th-century French painters

- French male painters

- Painters from Dordrecht

- Dutch romantic painters

- French romantic painters

- Dutch portrait painters

- French portrait painters

- Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- French philhellenes

- Academic art

- Burials at Montmartre Cemetery

- People of Montmartre

- Romantic painters

- 19th-century French male artists

- 19th-century Dutch male artists